The period in Argentina from 1880 to 1912 is known as the “Conservative Regime,” and in this article, we will examine some of its most important characteristics. We hope you find it helpful.

Why the “Conservative Regime”?

Many of the things done during this period were quite modern, so you might wonder why it is called the “conservative regime.”

This designation wasn’t used back in those days; it started being used later when this political group lost control of the country with the arrival of the Radical Civic Union.

After losing power, this group began to focus its political actions on preserving the old structures of the country (political, economic, and social). As a result, they started referring to their governing period as the “conservative regime.”

The “oligarchy” regime?

This is a concept that is currently being widely discussed, but it appears in most Argentine history textbooks, so it’s good to understand what it means.

When we talk about an oligarchy, we are referring to a government composed of individuals with significant economic power. Generally, it involves a small group of people who share a particular lifestyle, certain customs, and habits.

In Argentina, what could be called the oligarchy was a group primarily composed of landowners. These families owned vast expanses of land, which they often didn’t even work themselves, but instead rented out to earn a considerable sum of money. The Argentine oligarchy was mainly dedicated to livestock farming and cereal cultivation.

The fundamental difference with a peasant lies in the extent of land they own. As mentioned, landowners possess vast estates. Furthermore, peasants work themselves for their subsistence, while landowners do not necessarily do so.

The so-called “Conquest of the Desert”

With that name, the military conquest process that took over Argentine Patagonia remained in history. While it is true that it was a conquest, it wasn’t a desert as it was a territory inhabited by indigenous people. Thousands of indigenous individuals died during this campaign, losing their lands.

The “problem” with the indigenous people had started with the arrival of the Spanish, with the occupation of the territory by the white man. The first expeditions to expand the frontier took place during the time of Juan Manuel de Rosas. But the “Conquest of the Desert” referred to here was the one that occurred in 1878, ending a few years later. With this military offensive, they managed to control all the territory known today as Argentine Patagonia.

Initially, the advancement was led by Adolfo Alsina, who was the Minister of War under President Avellaneda. His idea was to establish successive lines of occupation, settling the conquered areas, and establishing military outposts. To defend themselves, they decided to dig a line of trenches, a kind of ditch called “the Alsina trench,” which was done in 1876.

Shortly after, Alsina passed away, and he was replaced by General Julio Argentino Roca, who would have a significant influence in the years to come. Roca decided to attack these territories with full military force and put an end to the “indigenous problem.” This was carried out to the letter, resulting in the killing of thousands of people who defended the territory that belonged to them.

In 1879, Julio Argentino Roca had to return to Buenos Aires because he was going to be a presidential candidate, being the great victor, the man who ended the “indigenous problem.” He stated in those years:

“We will seal with blood and meld with the saber, once and for all, this Argentine nationality that must be formed, like the pyramids of Egypt and the power of empires, at the cost of blood and the sweat of many generations.”

Julio Argentino Roca

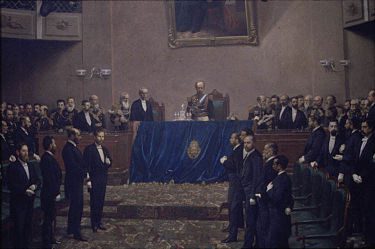

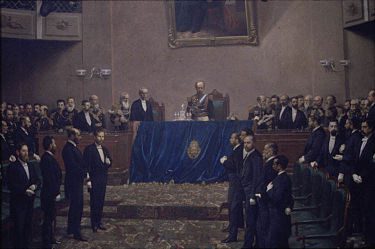

Politics during the Conservative Regime

In 1880, the year in which this period begins, Julio Argentino Roca was elected as president. As we saw, he was the military leader at the forefront of the “Conquest of the Desert.” He governed the country until 1886, and it’s worth remembering that for a long time in our country’s history, the presidential term lasted six years, not four as it is now.

After Roca, Juárez Celman was elected, who was his brother-in-law. This man governed from 1886 until 1890 when he had to resign after a significant event, the Revolution of the Park.

Both were representatives of the National Autonomist Party (also known as P.A.N. in spanish), and during this period, the political situation was very stable, thanks to the numerous agreements made among its members.

The Revolution of the Park

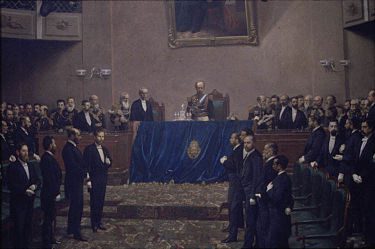

The Revolution of the Park was an armed conflict that began when a group of military personnel, accompanied by factions opposed to Juárez Celman’s policies, took control of the Artillery Park, located where the “Plaza Lavalle” is today in Buenos Aires. Although this movement didn’t ultimately succeed, the event was so significant that Juárez Celman resigned nonetheless.

This marked the end of a ten-year period of political stability, from 1880 to 1890. But the question that arises is, why was this group of people so angry as to attempt to seize power by force? The opposition group in question was the Civic Union, which would later become the Radical Civic Union (the same political party that exists to this day). At that time, it had the support of a small but influential sector of the armed forces.

Remember: After the Revolution of the Park in 1890, the nation’s president, Juárez Celman, had to resign. His successor was Carlos Pellegrini, the vice president, who completed the term.

The rebels disagreed with the government primarily because they were not allowed to participate freely in the elections.

Electoral Fraud

The National Autonomist Party resorted to electoral fraud to win elections, ensuring their victory. How did they do it? In various ways, they made the same individuals vote multiple times or prevented opponents from exercising their right to vote.

For example, it was common for a person to go to cast their vote, only to be told they had already voted. Worse yet, they knew exactly who they had voted for because the vote was not secret, as it is today. Instead, it was public: each person had to announce out loud whom they were voting for to the members of the polling station.

Faced with this situation, the opposition couldn’t participate freely, as they already knew in advance that they would lose. So, they exerted pressure on the government through force and demanded that the situation be made transparent to prevent further fraud. This is the primary reason for conflicts like the Revolution of the Park, and there were several others.

The Consolidation of the State

The consolidation of the Argentine State was also characteristic of this period, involving a process of constitution and professionalization of institutions such as the Armed Forces, education, and the establishment of federal courts. Additionally, bureaucracy was developed, and necessary public works were undertaken to demonstrate the presence of a “strong” State.

By 1880, the State established its headquarters in the city of Buenos Aires and from there defined its duties and taxes. On the other hand, in 1884, the Province of Buenos Aires established its government in the city of La Plata, which was built exclusively for this purpose.

The institutions that emerged in the late 19th century were:

Justice

The courts of first instance and courts of appeals provided prestigious positions to many politicians linked to the ruling power. Apart from those established in the capital, other courts were gradually established in major cities in the interior and later in the National Territories, with the aim of ensuring civil guarantees, individual rights, and teaching about the institutions of the National State.

Education

Through resources obtained from exports, the State took on the responsibility of carrying out the literacy process, and the growth of schools was rapid. The urgency in this regard was to advance primary education, or as it was known back then, elementary education. Later, a strong emphasis was placed on secondary education. Minister of Education Magnasco believed it was appropriate to set aside the study of Latin and prepare young people for official jobs with technical skills, understanding that the country would need them for its developmental stage.

Military System

Since the times of the May Revolution and National Independence, there were militarized groups; however, political tensions regarding the direction the nation would take led to the army not being national but rather partisan. By the late 19th century, due to the growth of the State and the need to protect the national borders, professional, technified, modern, apolitical, and national armed forces were required. Being apolitical was crucial, as they should not be influenced by “caudillos” or other political leaders from any part of the national territory. The definitive organization would only come in the 20th century.

National Bank

Carlos Pellegrini founded the Banco de la Nación Argentina, which promoted agriculture, livestock, industry, and commerce through financial incentives. The success of this institution was attributed to the careful oversight by the governments, exempting it from political commitments and granting it broad autonomy.

This is a summary of the conservative order in Argentina. We hope it has been helpful for you. Feel free to ask anything you need; we are here to assist you. See you in the next article!

This article was edited by the History.site team. We are from Argentina, so if you find any writing or translation errors, please let us know in the comments. Thank you!